By Nikos Jordan

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) is an organizational framework that has increasingly come under fire in recent years—and not for lack of good reason. As consultants working within this space, it is critical for us to acknowledge and work from the history and constraints—as well as urgent opportunities—that this field poses. Yet in order for us to understand the current state of the industry, we need to first understand its origins.

The first iterations of what could be called Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion trainings in the workplace emerged in the United States during the mid-1960s following the introduction of equal employment laws and affirmative action. Forged in a tumultuous period of politics and cultural shifts, these programs were intended to counteract unequal and discriminatory practices that were (and still are) embedded in predominant institutions as well as foster more integrated offices. As the Civil Rights, feminist, queer, anti-war, and other movements came into full swing in the United States during this period, institutions were increasingly impacted by their demands for equity and liberation.

Following the codification of inclusion into American law in 1972 with the Equal Employment Opportunity Act, organizations began to hire anti-discrimination practitioners to ensure compliance. With the realization of economic globalization and neoliberalism soon after in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the workplace focus of these germinal iterations of DEI shifted focus from integration to diversity. As national corporations evolved into multinational entities, the imperative to broaden inclusion initiatives beyond “racial integration” within an American context became evident. This period witnessed the emergence of employee resource groups concentrating on gender, sexual orientation, and a variety of racial demographics, transforming the predominant discourse surrounding inclusion. The term “integration” was no longer deemed sufficient; there arose a necessity to address “diversity.”

“Integration” in the context of the United States in the 1960s and 1970s referred to the inclusion—primarily of Black or African Americans but also of other ethnic groups—into predominantly white institutions. This was a response to the Civil Rights movement, though “integration” during this time was still marred by tokenism, assimilation into institutions defined by white masculinity, and superficial notions of inclusion that did not address systemic racism. These features still haunt DEI efforts to this day.

Since then, the concept of DEI has become a commonplace framework that many organizations have engaged with on at least some level. Yet when it comes to concrete improvements in the societal position and liberation of marginalized peoples, remarkably little progress has been made. In many instances, the state of marginalized peoples has merely worsened. However, this should come as no surprise; while kickstarted by visionary Black leaders, revolutionary feminists, and queer people, the aspirational beginnings of what would come to comprise the framework of DEI quickly became ensnared in a vortex of capitalism and compliance, globalization and neoliberalism. When tempered and nulled by forces that do not allow for deep negotiation, it is inevitable that the outcomes of DEI initiatives—however driven by goodwill they may be—ultimately fall flat and fail to deliver large-scale, tangible results for the people who they are allegedly designed to serve.

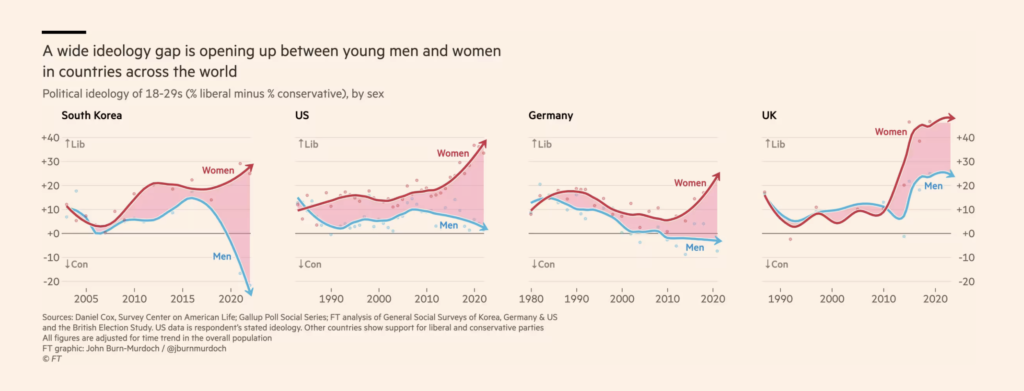

There are other interrelated issues with DEI that have received increasing attention in the public discourse in recent years, such as the frequent domination of the field by white women and the trappings of its Western and US-centric methods. This is all occurring at a time when racism and discrimination is steadily on the rise globally, a record number of legislations against queer and gender non-conforming people are being established, climate and biodiversity crises are wreaking existential threats, new political gender divides are widening in younger generations, violence is increasing within an exponentially polarized world, and the results of predominant DEI frameworks are failing to engender substantive change.

Yet the common refrain we hear in the midst of this societal pendulum swing is that it is the principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion themselves that are the problem, not the violent and inequitable structures that any and all effective DEI initiatives should be aiming to deconstruct. This places us in a rather precarious position; how can we recognize the real faults of DEI without abandoning its aims all together? How can we ensure that everyone understands themselves as intrinsically bound to the fate of these systems and that any privilege gained within them does not truly bring them or any of us forwards? While perhaps more unpopular than ever, DEI is perhaps needed more than ever—but not in the way it has conventionally been done.

While perhaps more unpopular than ever, DEI is perhaps needed more than ever—but not in the way it has conventionally been done.

This is where decoloniality comes in. However, many people have never heard of decoloniality. While decolonization is a more commonly recognized term, there are key differences between the two. Before understanding either, it is essential to acknowledge all of the ills currently plaguing society—from the collapse of ecosystems to the invention of race—have derived from the European colonial empires which metastasized globally between the 15th and 20th centuries and set a model for “development” that has not been abolished but merely reformed. While their direct rule over the rest of the world has changed forms, we are far from living in a “post-colonial” world. Beneath all of the stratifying forces and expansions of violence inherent to racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, anthropocentrism, and more lies the bedrock of the contemporary world that we have inherited: the legacy and present violences of colonialism.

While decolonization may be defined in relation to the return of land to Indigenous peoples and is temporally determined and geographically focused, decoloniality is discerned in relation to colonial ways of thinking and being that remain and animate both the colonized and the colonizer even after processes of decolonization. Decoloniality involves questioning and deconstructing colonial ways of being and thinking (coloniality) while resurrecting ancient knowledge systems, centering those that have been marginalized, and fostering alternative futures rooted in justice and equity.

Composing the pillars of our socioeconomic system, the realities of colonialism are forces that have binarized the world in a hierarchy of power and demanded us to offer an alternative—not just for our collective liberation but for our very survival. When we critically examine the constructs DEI alleges to deconstruct—racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, and more—we come to see them as inextricably bound to the forces of coloniality. What was the world before such inventions? Who were we before who we were was made to be a problem? Where do we go from here?

This is why we call ourselves Beyond DEI; we recognize that the world we need to realize lies beyond current paradigms of “change.” The world we need to realize is intersectional, decolonial, collective, personal, ecological, liberatory. It is not only the deconstruction of what has been but the resurrection of what once was and the generation of what has never been but could be. This world beyond is what is demanded of us at this moment in time, and the Earth and its people need it. Our approach at Beyond DEI is based on this fundamental recognition, and our mission is to revolutionize the field of DEI to meet the crises of our time and fulfill the promises of diversity, equity, and inclusion that have been unrealized through prevailing frameworks.